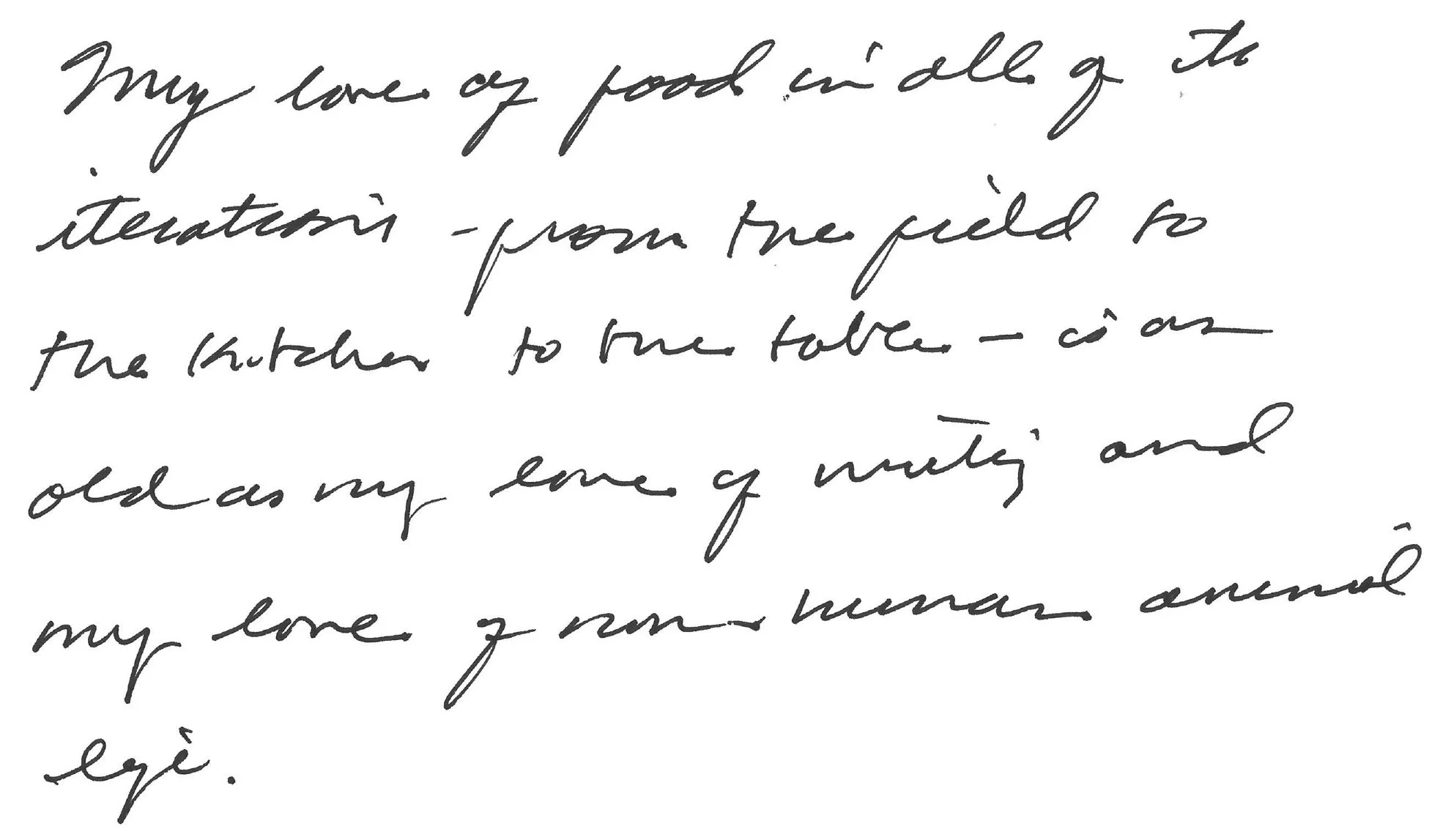

My love of food in all of its iterations – from the field to the kitchen to the table – is as old as my love of writing and my love of non-human animal life. Raised as a child in what was known as “the chocolate city,” (Washington, D.C.), I spent my summers in Durham, N.C. with my beloved grandmother who was not only the centerpiece of her small community, but also my foodie world. My first memories of my “Nana” are of her in front of the great General-Electric six burner double-oven range, instructing me in how to sear and simmer. She introduced me to hulling beans, selecting fresh fish and well-produced poultry. It is her farmer’s market, so different from today’s rather pristine undertaking, that is my first and enduring memory of what it means to truly be a cook’s cook.

In college, I no longer split my time between Washington, D.C., where I was born and grew up, and Durham, North Carolina. But I brought what I learned from cooking with my grandmother – and watching Julia Child and Jacques Pépin on public television – to New Jersey, cooking in the basement once a month for anyone who wanted to eat.

For the most part, my foodie life moved alongside my academic one. I was determined to have food be my source of joy rather than “work.” I did not want to make of it a “career” that would then become a soul-crushing endeavor filled with deadline-driven desires, instead of more hedonistic ones. After years of cooking with others, and cooking alone, of sharing meals with colleagues and friends, I created my blog, theprofessorstable (2011), to celebrate my love of writing, cooking, and all things equestrian.

The blog grew into what is now Those Who Eat, a new project that tells the story of my decades-long obsession with and memories of food.